|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

Lost Japan (English)

|

Introduction |

Articles & Reviews

This important work, originally written by its author in Japanese, and here translated back into English, is a deeply personal witness to Japan's willful loss of it traditional culture >>

Alex Kerr came to Japan as a 12-year old schoolboy in 1964. Like so many before and after him he was here because of the US military. His father was in the U.S. Navy. The Japan he found then enchanted him.

It's a curiosity of writing on Japan that many of the finest books by foreigners are laments: sighing, nostalgic elegies for a vanished world of delicate beauty, lost forever beneath a tidal wave of industry, development and glib Westernization, As early as the Meiji Era, the British >>

When I saw the title and first looked at this book, I was inclined to dismiss it as yet another nostalgic volume about old Japan, deploring all things modern and materialist with little new to say about Japan today. I have to admit that once I started to read Alex Kerr's book I realized >>

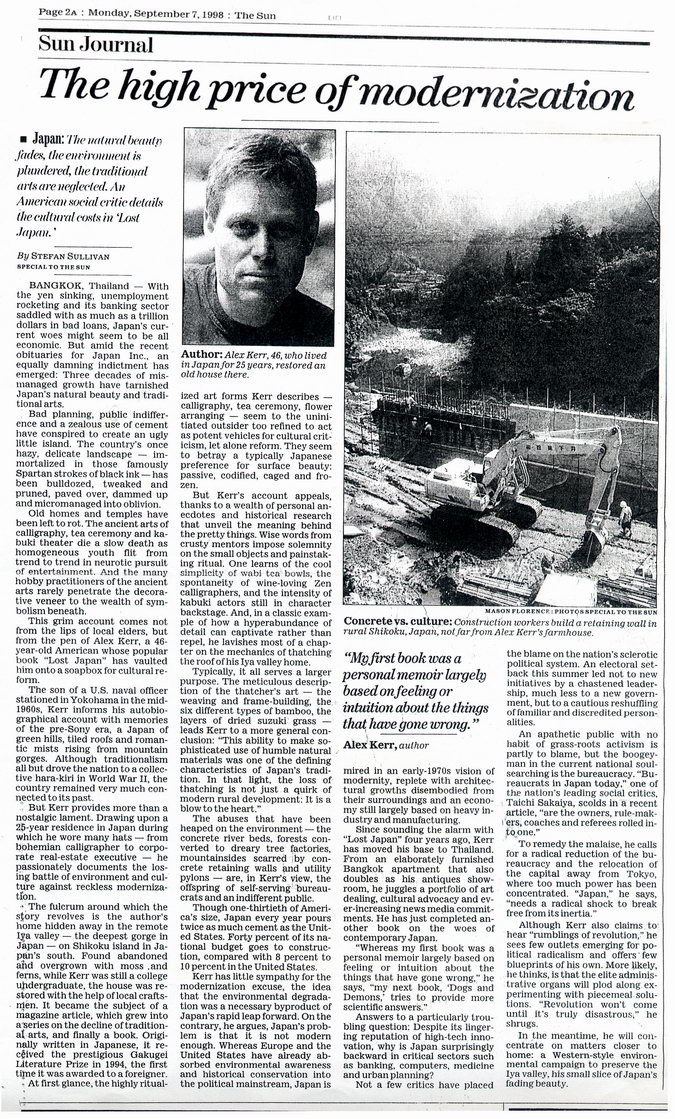

Japan: The natural beauty fades, the environment is plundered, the traditional arts are neglected. An American social critic details the cultural costs in 'Lost Japan.' "My first book was a personal memoir largely based onfeeling or intuition about the things that have gone wrong." Alex' Kerr, author

Japan Times Richie, 1995 May 28

Kansai TimeOut, 1996 June

Tokyo Journal, 1996 Aug

It's a curiosity of writing on Japan that many of the finest books by foreigners are laments: sighing, nostalgic elegies for a vanished world of delicate beauty, lost forever beneath a tidal wave of industry, development and glib Westernization, As early as the Meiji Era, the British Japanologist Basil Hall Chamberian announced that "Old Japan is dead and gone," and the same sentiment has provided fodder for literary gaijin over more than a century.

In the 1960s Donald Richie's travel classic, The Inland Sea, described the vanishing innocence of rural Shikoku in the years before it was joined to the mainland by the Seto-Ohashi bridge.

Fifteen years later, Edward Seldensticker marked the passing of old Tokyo in Low City, High City and Tokyo Rising, while Looking For The Lost by the Late Alan Booth turned a desolate eye on the state-sponsored vandalism wrought on the Japanese countryside. [Actually the tendency goes way back to medieval Kyoto and the cult of mono no aware - the 'transience of things' plan gently celebrated in the Tale of Genji.) But for all the elegant tears shed over its passing, there always seems to be enough doomed beauty left for the next generation to fret and agonize over. In Japan, It is axiomatic that Things Aren't What They Used To Be.

So it's with a certain skepticism that one turns to Alex Kerr's book. From Its title to its back-cover blurb {"exposes the environmental and cultural destruction that is the other face of contemporary Japan"}, it looks [like the classic gaijin elegy. But Lost Japan is a true original, a rich blend of art criticism, social history, memoir and polemic, by one of the most interesting foreigners in Japan.

Published originally in Japanese as a series of articles for a monthly magazine, the book takes the form of 14 essays, each focusing on an aspect of the author's life since his first arrival here as a 12-year-old military kid in 1964 The Olympic year was, Kerr later realized, a pivotal one, when "the imbalance between city and rural incomes passed a critical point, and farmers all over Japan fled the countryside." The consequences of this depopulation were devastating - "These days," he observes, "all of rural Japan gives the impression of becoming one enormous senior citizens home." But for Kerr, this was also an opportunity.

in the early l970s, as a near-penniless student, he bought and personally restored an abandoned house in the Iya Valley in Shikoku. even now one of the remotest in the country Nothing is so flattering as the lens of nostalgia but, even so, Kerr's tenderness for this time is convincing "Mist boiled up out of the valleys as if by magic; the slender and delicate tree branches quivered like feathers in the wind.

It felt as though at any moment a pterodactyl might come flying out of the mist... If I live to be 80 or a 100, I doubt that the lost beauty of Japan's mountains and forests will ever fade from my memory

Within ten years, though, the idyll was over. Roads were cut through the mountains, rivers and mountain sides were gummed over with concrete dams and erosion walls. The jungly, primeval forests were cut down and replaced with rows of uniform cedars. "deserts in which the living breathing presence of plants and animals cannot be sensed." and the natural wood and thatch of the old houses disappeared under a layer of plastic and aluminum.

The obvious perpetrators of this systematic destruction-rural Diet members who keep their supporters happy with a steady supply of point-less public works projects-do not interest Kerr.

Instead he focuses on the deeper, cultural reasons for the country's uglification. industrialization

came so quickly that the Meiji Japanese had no chance to acclimatize As a consequence, although their great-grandchildren "may admire the ancient cities of Kyoto and Nara deep in their hearts they know that they have no connection to their modern lives.. these places have become cities of illusion, historical theme parks."

Meanwhile the traditional skins and aesthetics that built these ruined masterpieces are confined to museums-and to the real theme parks. Sent by a magazine to write a sarcastic denunciation of Huis Ten Bosch, the painstakingly recreated "Dutch village" near Nagasaki, Kerr is stunned to find it "perhaps the single most beautiful place I have seen in Japan in 10 years... As living cities like Kyoto decay, they will be replaced by copies.

As an art collector, Kerr's great pleasure is in juxtaposing his treasures "Arranging them with their essential meaning and artistry in mind, (so that] the world of the literat Kyoto court nobles comes to life" This is also his talent as a writer-the dilettante's ability to make entertaining and illuminating connections. bridging abysses of time and subject matter. Motoring through the Kansai countryside, for example, on a pilgrimage to the ancient temples, Kerr is confronted with the neon facades that dominate even the smallest towns. In Europe, the highest building in the village is always a church; "In the Japanese countryside. however, the tallest and most ostentatious building is inevitably a pachinko parlor." This leads to a digression on the appeal of pachinko-"the modern form of meditation. The circular arrangement of the pins. . is today's version of the mandala." And so, by way of architecture, pinball and meditation, we are back where we started, with Buddhism.

Kerr's autobiography would be fascinating in itself. In the 30 years since his first visit, he has hitchhiked from Hokkaido to Kyushu, restored two traditional houses, run an art-dealing business, worked for a Shinto foundation, exhibited his own calligraphy, and sold property for a Texan estate agent. He has befriended Kabuki onnagata, Korean poets, Osaka bankers. Tibetan lamas, Kyoto tea masters, and the Burmese dissident Aung San Suu Kyi, and he divides his time between Tokyo and his rural retreats in Kansai and Shikoku. As an authentic modern day hermit-sage, he is effortlessly learned [just occasionally, the sprinkling of Chinese sayings and erudite references ("When the late Kanzaburo XVII prayed Kumagai. ") verge on serf-parody], but there is never a trace of prissiness, and the narrative races along, neatly balancing critical analysis and personal anecdote.

As an intellectual, Kerr is a rambler rather than a mountaineer, and the least satisfying parts of this book are its conclusions. The account of selling real estate in '80s Tokyo is one of the best and simplest accounts so far of the famous 'Bubble,' but the doomy suggestion that its puncturing" is a prelude to a revolution" is vague and unconvincing. Even Kerr's passionate account of the decay of the Japanese arts is undermined by the sudden and weakly argued assertion that "at the very moment of its disappearance, Japanese traditional culture is having its greatest flowering." In fact, as the author himself points out, "my ability to keep collecting depends on just one thing: the lack of interest in Asian arts displayed by the Japanese." An ever-replenishing sense of loss is part of the culture and Alex Kerr. I suspect, would not have it any other way.

by Richard Lloyd Parry

Asian Affairs, 1997 June

When I saw the title and first looked at this book, I was inclined to dismiss it as yet another nostalgic volume about old Japan, deploring all things modern and materialist with little new to say about Japan today. I have to admit that once I started to read Alex Kerr's book I realized that this snap judgement was unjustified. While there is nostalgia, and while to many of us who have spent the bulk of our lives in or to do with Japan much of what Kerr writes is familiar, this book does contain interesting sidelights on Japan today and cannot be simply dismissed as another travelogue.

Kerr is right in stressing the tragic destruction of much of Japan's natural environment. Japanese art and culture are so bound up with nature that the inevitable result must be a degrading of aspects of Japan's cultural tradition.

We can also sympathize with his enthusiasm for kabuki, for the restraint which is such an important element of Japanese art, and for collecting Japanese and Chinese art.

Kerr is perceptive in his descriptions of the problems encountered in a joint venture between Sumitomo Trust and the American company Trammell Crow. I liked the story of the American property man who had been talking about square feet of space and was frustrated by what he thought was a discussion of "soup bowls". The Japanese were, of course, referring to 'tsubo', the unit of land measurement still used in Japan.

Kerr points out the real dangers arising from a long tradition of isolation, from cozy business and governmental relationships, from an over-emphasis on consensus and from Japanese over-regulation. He notes (p. 167) that: "below is rising desperation on the part of a generation that has some knowledge of the outside world and realizes that Japan is falling behind".

Of his reaction to Huis ten Bosch, a Dutch theme park in Japan, he writes (p.183): "Huis ten Bosch was everything the new Kyoto is not - namely, peaceful, and beautiful. To my great embarrassment as a lover of Japanese art, I could hardly bear to leave the place." He quotes the kabuki actor Tamasauburo as saying: "Kyoto is beyond preservation. The next step will be recreation", but will the recreation be alive and beautiful or dead and boring? Kyoto and Nara are, of course, special to all Japanophiles and I could take issue with some of Kerr's preferences in these two ancient capitals, but I will confine myself to quoting one of his Kyoto stories (p. 250). He was talking about antiques one day at a tea house with a Japanese woman who said that her family had had a wonderful collection of antiques but they were all "destroyed in the last war". Kerr was naturally puzzled as Kyoto had escaped bombing during the war.

The master whispered in his ear: "By the last war she means the Onin war" (a mere 500 years ago!) Readers of Asian Affairs who know something of Japan and want a readable and interesting personal account might put this book in their holiday luggage. But they should not take it as a substitute for a guide, which it is not and which it does not claim to be.

HUGH CORTAZZI

The Sun, 1998 Sep 7

|

|

|

|

|

|