|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

Dogs & Demons (English)

Tales from the Dark Side of Japan (Hill and Wang)

The Fall of Modern Japan (Penguin UK)

|

Introduction This book tells the tale of Japan's malaise since 1990. It combines a study of the financial world, the bureaucracy, and culture, to get at the roots of Japan's modern troubles. |

Articles & Interviews

Alex Kerr's Dogs and Demons is a seminal study of how the combination of bureaucrats, politicians and business interest can use self-interest to destroy the future of a country. That country is Japan. Kerr's account is poignant, incisive, brutal and beautiful at the same time.,

Thanks for joining this exchange, and thanks for writing the book. While reading it, I was struck both by material that was very fresh and by themes that were very familiar. I mean both points in a positive sense. The facts, anecdotes, and revelations will strike most readers as fresh and new. At least many of them struck me that >>

The subtitle of Alex Kerr's new book is, appropriately, "Tales From the Dark Side of Japan." The latest effort from the author of the award-winning "Lost Japan" provides keen insight into the unique causes and disastrous results of the once heralded >>

REMEMBER THE DAYS WHEN Japan seemed all-powerful? If your memory is a bit hazy, it's hardly surprising. Just like many Germans for whom the Berlin wall has quickly receded into history and taken on a fairy-tale quality, >>

An ancient Chinese tale holds that dogs are difficult to draw because they are ubiquitous; demons are easy to create because they spring from the artist's imagination. Or, to put it more plainly, it is difficult to focus on the mundane and familiar, but quite easy to envision the grand, the colorful and the unique. >>

Alex Kerr has given us a remarkable portrait of modern Japan, virtually no part of which is flattering. As his subtitle indicates, he goes out of his way to catalog the dysfunctions that dominate an unhappy and declining country. ''Dogs and Demons'' (from an inaccessible Chinese metaphor) will not be welcomed >>

"Unlike some Japan watchers ... Mr Kerr does not blame Japan's economic and cultural malaise on its attempts to "catch up to the West". To the contrary, he argues - with style and wit - that Japan is floundering precisely because it has failed to adapt, both technologically and socially, to the demands of the "modern" world." >>

Christopher Moore's blog, Dogs & Demons, 2007 Jan 24

Alex Kerr's Dogs and Demons is a seminal study of how the combination of bureaucrats, politicians and business interest can use self-interest to destroy the future of a country. That country is Japan. Kerr's account is poignant, incisive, brutal and beautiful at the same time. He draws upon both ancient and modern Japan to paint a picture of a country without zoning or sign control, pollution regulation, a country which has destroyed its forest, rivers, and sea coast. Kyoto is transformed from the ancient city spared by the American bombers in World War II into a shabby, trashy city with ugly apartment blocks, bulldozing the green spaces, and tearing down the ancient wood houses that once defined Kyoto. The allied bombers would not have done a better job. Kerr takes the reader through the inside world of inside dealing where civil servants and big businesses work together, share ownership, and control over budgets and resources. The stench of corruption rises from these relationships and the damage done from the conflict of interest is difficult to calculate.

Kerr describes the elite's war on nature in Japan:

"Take the ideology of 'An Archipelago of Disasters' and marry it to 'Total Dediction.' Sweeten the match with dowry in form of rich proceeds to politicians and bureaucrats. Glorify it with the government-paid propaganda singing the praises of dam and road builders. The result is an assault on the landscape that verges on mania; there is an unstoppable extremism at work that is reminiscent of Japan's military buildup before World War II. Nature, which 'wreaks havoc' on Japan, is the enemy, which rivers in particular seen as the 'true ban of Japanese life,' and all the forces of the modern state are made to focus on eradicating nature's threats."

This is an angry, elegant, compelling book; rich in persuasive detail and antidote. Kerr has spent more than 30 years in Japan. He started as a schoolboy. His fluency in Japanese is unrivalled by all but a handful of foreigners; his passion, insight, and dedication to Japan matched by none. If you wish to have your eyes opened to the inside, secret Japan and what has happened in that country since World War II, this is the perfect book. It will be impossible to close your eyes to the reality once you've read it. The book has caused a storm of controversy in Japan. And Kerr is frequently asked to speak before various groups, public and private, as he was the first to ring the alarm bell.

http://www.cgmoore.com/blog/index.asp

Brief Comments by the Critics

"Dogs and Demons is a must read for anyone with even a cursory interest in the rise and continued fall of postwar Japan"

Michael Judge, Wall Street Journal

"Japan's political leaders have caused the country and its people to pay a

terrible price. The cost is here verified in a scrupulous accounting which

honestly recounts just what happened."

Donald Richie

"Alex Kerr's Dogs and Demons succeeds like no other account of Japan in

conveying the tragedy of a scrupulous and well-intentioned people cursed

with a headless system of governance'. Let us hope for the Japanese as well as the rest of us that it contributes to a cause that we might call 'regaining common-sense'."

Karel van Wolferen

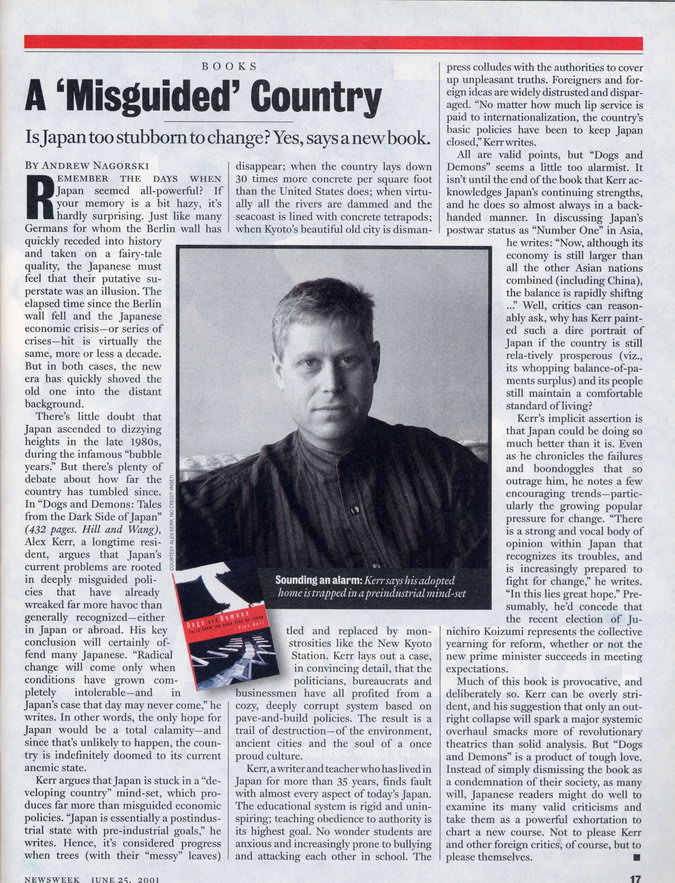

"Kerr lays out a case, in convincing detail, that the politicians,

bureaucrats and businessmen have all profited from a cozy, deeply corrupt

system based on pave-and-build policies ... Much of this book is provocative, and deliberately so ... But Dogs and Demons is a product of

tough love'

Andrew Nagorski, Newsweek International

"Kerr has produced what will be a very controversial work and many are

likely to brand him anti-Japanese. Nothing could be further from the truth

... Dogs and Demons is a passionate cry for help by a man who cares very

deeply about Japan and ordinary Japanese people."

Eric Johnston, Japan Times

"A tough book, but one that can tell us a huge amount about contemporary Japan"

Jan Dalley, Financial Times (London)

"Kerr plunges headlong into the self-destruction that is threatening to

leave once-beautiful Japan in the dot-com dust of the 21st century ... His

honesty in describing delicate internal issues is a refreshing change from

the myriad "experts" who have published prescriptive and predictive books on Japan in the past 20 years."

Nina Kahori, JAPAN Magazine

"Unlike some Japan watchers ... Mr Kerr does not blame Japan's economic and cultural malaise on its attempts to "catch up to the West". To the contrary, he argues - with style and wit - that Japan is floundering precisely because it has failed to adapt, both technologically and socially, to the demands of the "modern" world."

Michael Judge, Wall Street Journal

"One of the reasons your book deserves attention from a Western readership is precisely how different it sounds from the run of general reporting about Japan ... I do hope people will get and read the book. It's gracefully written and well-informed. It's full of original observations."

James Fallows (from Fallows @large, Atlantic Unbound website,

email exchange with author)

New York Times, 2001 Apr 15

By RICHARD J. SAMUELS

Land of the Setting Sun?

Published: April 15, 2001, Sunday

DOGS AND DEMONS:

Tales From the Dark Side of Japan.

By Alex Kerr.

432 pp. New York:

Hill & Wang. $27.

Alex Kerr has given us a remarkable portrait of modern Japan, virtually no part of which is flattering. As his subtitle indicates, he goes out of his way to catalog the dysfunctions that dominate an unhappy and declining country. ''Dogs and Demons'' (from an inaccessible Chinese metaphor) will not be welcomed in the polite company of those who prefer to powder Japan's happy face.

Kerr, the author of ''Lost Japan'' and a longtime resident of Japan, confidently cuts a broad swath across the worlds of architecture, education, politics, cinema, business and the environment to make the case that Japan has fallen victim to its own success. The problem is that form (kata) dominates function and purpose (jitsu) in every nook and cranny of Japanese life. What is left is empty: memorization without learning, design without context, building without purpose, information without knowledge, finance without the production of value. Bombast has overwhelmed understatement, and all is pure manga -- comic-strip fantasy, trashy, cheap and shiny.

Kerr has a keen eye for paradox. Japan is today a high-tech economy that lacks the know-how to test for toxic waste, a ''postindustrial country with preindustrial goals.'' It is an industrial battleship on faulty autopilot. But it gets worse. Kerr's Japan is a land of prevarication: the government tells children that plutonium is safe to drink. It is a land of duplicity: retired government officials skim profits from public-works spending. It is a land of incompetence: wooden ladles and plastic buckets are used to clean up after nuclear disasters and oil spills. It is a land of collusion: industry and government join to hide the poisoning of innocent citizens. It is a land of widespread intimidation: students are afraid to subscribe to environmental magazines for fear that it will hurt their career chances. And it is a land without transparency: in response to demands for audits, officials torch public records with impunity and police departments develop training materials to teach officers how to cover up scandals.

As with most polemics, Kerr's is riddled with hyperbole. He force-feeds us a cartoon version of how Japan is governed -- by ''near dictatorial'' bureaucrats -- when, in fact, the system goes forward because politicians win re-election for delivering concrete goodies: roads, schools, community centers, hospitals. If Japan is a nation gripped by a ''boondoggle fever,'' that fever is one voluntarily induced and willingly endured.

Kerr also overstates the dysfunctions. Japan still has a lower crime rate, a healthier diet, cleaner city streets, longer life expectancy, better mass transit, higher literacy and more equitable income distribution than virtually any other industrial nation. And the Japanese government has already begun to rectify its environmental insouciance in ways Kerr dismisses as inconceivable.

Besides, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Kerr skillfully evokes a bleak, cluttered and tawdry environment. But he treads dangerously on (and often steps over) the fine line between trenchant criticism and the imposition of his own aesthetic values. Many who have traveled as extensively as he will not agree that Japan is ''arguably the world's ugliest country.'' They will be annoyed at the way he understates the beauty that remains -- the hot-spring resorts, the Okinawan beaches, the mandarin orange groves dotting the rural landscape and the immaculate grounds of Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines suddenly encountered in even the most ''jumbled'' urban setting.

That said, Kerr has packed his book with lucid observations. It is fascinating how Japan's built space is either old or new, but never restored. It is alarming that the level of carcinogens in the air around Kobe after the 1995 earthquake rose to 50 times normal levels because Japanese builders continued to use asbestos materials long after they were banned elsewhere. It is extraordinary that the museum most frequented by Japanese is the Louvre -- far from home-grown package tours of dams and concrete river fortifications.

Kerr offers up sometimes astonishing comparisons, like data that suggest planned spending in Japan on public works in the next five years will exceed that in the United States by 300 to 400 percent, despite there being only a twentieth as much land area to be manipulated. The Japanese lay 30 times as much concrete per square foot as does the United States, and Japanese spending on public works exceeds American spending on the space program.

But Kerr misses the chance to use his comparisons even more effectively, for his arguments repeatedly evoke the United States' own shortcomings. Americans of a certain social class often complain that regional character has been wrung out of American life. They bemoan how any mall off any Interstate is home to the same Banana Republics, Sunglass Huts and Starbucks. The ''cultural meltdown'' of Kerr's Japan may be more painfully familiar to Americans than he acknowledges.

Nor is policy inertia unknown to us here. Whether Japanese politicians are building dams or American ones are building bombers, both are responding to the same electoral imperatives. In each case, dipping into the public trough to appease constituents has led to white elephants.

Despite Kerr's claim to novelty, ''Dogs and Demons'' is but the latest in a series of broadsides (for example, Ivan Hall's ''Cartels of the Mind,'' Norma Field's ''In the Realm of a Dying Emperor,'' Karel van Wolferen's ''Enigma of Japanese Power'' and Edward Seidensticker's ''Low City, High City'') that correct the wide-eyed and superficial celebrations of Japan's great success. There will (and should) be more, for it is not only the economic bubble that burst in Japan during the 1990's. So did the market for books about Japan's mastery of the universe.

But one must ask: How satisfying would a portrait of American culture and politics be if it described only corporate cover-ups, reality television, racial profiling, misogynistic rap lyrics, widening income disparities, electoral miscounts, police brutality, glass ceilings, suburban sprawl, hate crimes and the excesses of the Las Vegas strip? While each of these is a slice of the contemporary American pie, they add up to less than the full plate of national life. So it is with this important and oddly romantic, if imbalanced, book.

Richard J. Samuels, the director of the Center for International Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, is the author of ''Rich Nation, Strong Army: National Security and the Technological Transformation of Japan.''

Japan Times, 2001 May 27

By ERIC JOHNSTON

Japan's traditions aren't lost, they're buried

DOGS AND DEMONS: Tales From the Dark Side of Japan, by Alex Kerr. Hill and Wang, 2001, 432 pp., $27 (cloth).

An ancient Chinese tale holds that dogs are difficult to draw because they are ubiquitous; demons are easy to create because they spring from the artist's imagination. Or, to put it more plainly, it is difficult to focus on the mundane and familiar, but quite easy to envision the grand, the colorful and the unique.

Applying such wisdom to the economic and social development of an entire country might seem like a dubious task. But Alex Kerr succeeds brilliantly. He argues that Japan's obsession with building "demons" like worthless public-works projects, while ignoring "dogs" like low-key activities that help preserve the environment and traditional culture are the real cause of not only Japan's "Lost Decade," but of a deeper crisis that he defines as cultural malaise.

Kerr, whose previous book, "Lost Japan," was the first publication by a foreigner to win the Shicho Gakugei Literary Prize for nonfiction, is no ordinary Japan observer. With over 35 years firsthand experience living in or dealing with the country, he has watched, with increasing rage, as Japan's obsession with economic growth and public works has led to environmental and social degradation and an estrangement from the rest of the world and the nation's true self.

He begins with an examination of Japan's obsession with construction -- that huge, bloated monster of an industry that pours concrete over every riverbed, forest and harbor it can find. Disregarding environmental law, scientific analysis, economic need, popular opinion and ordinary common sense, the Construction Ministry, and especially it's powerful River Bureau, orders projects like the Nagara Dam to proceed despite public opposition and little evidence of need. Since nearly 40 percent of combined national budget expenditures go to public-works projects -- the comparable figure in the United States is about 9 percent -- all the ministries have a strong incentive to build just for the sake of building.

Even when concrete is not being poured, the Japanese obsession with rearranging the landscape often leads to environmental disaster. Consider a plan, introduced by the Forestry Agency in the late 1940s, to clear the natural forests on mountain sides and plant commercial timber. By 1997, Japan had replanted nearly half its broadleaf forests with coniferous trees, primarily cedar. But the acidity of the cedar trees damaged the surrounding wildlife, creating a barren desert free of plants, bushes and grass underneath the trees.

Unable to hold ground water, mountain streams beside the newly planted trees have dried up, a phenomenon known as "cedar drought." The cedar trees, which officials originally said would provide work for those in the countryside, are still standing because over the past 50 years those who the government thought would be cutting trees left for less dirty and dangerous work in the big cities.

The demons come most clearly into focus when Kerr demonstrates how the construction state mentality has extended to aspects of Japanese cultural life. Most hideous is the state of Japanese architecture. Although there was a brief period in the 1960s when Japanese architecture won international acclaim, Kerr shows how the jumble of incoherent buildings that have been thrown up since then stem from the minds of individuals who lack any aesthetic sense of balance.

In two chapters on the philosophy of monuments and the business of monuments, Kerr argues there are two basic forms of monument in Japan: manga and massive. The former is distinguished by functionless decorations such as stainless steel tubes topped with dragonheads at a sword museum in Yokota. The latter includes massive buildings like those planned for Tokyo and Osaka harbors. These may be an architect's ultimate fantasy, but they're a city's financial nightmare.

Many of these monuments were conceived during the years of the bubble economy, roughly 1987 to 1991, a period that Japanese are now desperate to forget. In what should be required reading for anyone who writes about or studies the Japanese economy, Kerr recounts one of the most unbelievable tales of that gilded age: In 1987, just as the bubble was inflating taking off, Japan's leading bankers and industrialists descended upon one Onoe Nui in Osaka, who gave them stock advice that came from a ceramic toad.

You didn't misread that: a ceramic toad. As Kerr explains, in China and India, toads are believed to have mystical powers and none had more power over markets than Nui's toad. Top officials made regular trips to a remote Osaka neighborhood where the toad, through the body of Nui, told them how to invest. Thus, the financial fate of a nation was divined -- until Nui got greedy and someone finally woke up and had her arrested.

From there, things went downhill for Japan. Deftly avoiding economic and financial jargon, Kerr explains in clean, precise language how, with the demise of Nui's toad, the Finance Ministry and corporate Japan have cooked, fiddled and juggled the books in a vain attempt to convince the Japanese public and the international business community that all is well.

For Kerr, the reason Japan fell from its position as an economic power so far so fast is a product of its history and culture. An emphasis on shared responsibility and obedience led to a situation in which no one is in charge. As a result, once Japan sets out on a course, it will not stop. Since the Meiji Period, Japan's unbridled race to catch up with the West and become "modern" has created a mentality in which the world's second-wealthiest nation in terms of per capita income believes it is still poor.

In a passage that will surely enrage both politically correct American scholars and graduate students in East Asian study departments as well as Japan's rightwing conservatives, Kerr argues that Japan has a problem with honestly looking at and dealing with unpleasant truths. The old shibboleths of "honne" and "tatemae" are presented as yet more evidence that Japan simply cannot avoid carrying things to extremes. Tatamae, he notes, is fine when one has committed a faux pax in polite company. But it's disastrous when applied to national finance and sound environmental and social policies.

It would be easy to dismiss much of Kerr's work as science fiction or the rantings of someone who has spent too much time in Zen gardens. But like Karl von Wolferen's classic "The Enigma of Japanese Power," "Dogs and Demons" pulls together concerns and criticisms thoughtful Japanese and foreign observers have long held about separate aspects of Japan (the economy, the environment) and shows how they are symptoms of a much more deeply-rooted problem: that of Japan's identity.

Kerr admirably resists the temptation to give readers a happy ending by providing easy answers or offering advice. Instead, he simply notes that the Japanese will have to find their own way out of the concrete, Pokemon Orwellian nightmare that Japan has become.

This approach makes "Dogs and Demons" one of the most worthwhile books on Japan in quite some time. Kerr has already come under attack from certain American academics (notably, Harvard's Ezra Vogel) for painting too bleak a picture. Others in the U.S. and Japan will no doubt cry "Japan basher!" upon reading this book.

In the introduction, Kerr anticipates his critics, charging that too many people who claim to be friends of Japan are more interested in mouthing platitudes and tired stereotypes so that they might not lose their university grants, symposium invitations or business contacts.

Yet as anyone who has lived in Japan will admit, most of the problems detailed in "Dogs and Demons" are very real. In the finest traditions of investigative journalism, Kerr has produced what will be a very controversial work and many are likely to brand him as anti-Japanese. Nothing could be further from the truth. Kerr, like von Wolferen, is one of Japan's true friends. "Dogs and Demons" is a passionate cry for help by a man who cares very deeply about Japan and ordinary Japanese people.

Newsweek, 2001 Jun 25

Wallstreet Journal, 2001 Jun 25

by Michael Judge

The subtitle of Alex Kerr's new book is, appropriately, "Tales From the Dark Side of Japan." The latest effort from the author of the award-winning "Lost Japan" provides keen insight into the unique causes and disastrous results of the once heralded "Japan Model" of development.

Educated at Yale, Oxford and Japan's Keio University, the author. as the book's jacket attests, has "lived among" the Japanese people for 35 years. It shows, both in the depth of his understanding and degree of frustration with a top-down system that discourages accountability and has devastated the environment, the economy and, perhaps most important, the spirit of the Japanese people.

Unlike some Japan watchers, however, Mr. Kerr does not blame Japan's economic and cultural malaise on its attempts to "catch up to the West." To the contrary, he argues that Japan is floundering precisely because it has failed to adapt, both technologically and socially, to the demands of the "modern" world.

In the book's prologue he writes, "Japan's way of doing things-running a stockmarket, desiping highways, making movies - essentially froze in about 1965. For 30 years, these systems worked very smoothly, at least on the surface. Throughout that time Japanese officialdom slept like Brunnhilde on a rock, protected by a magic ring of fire that excluded foreign ifluence and denied citizens a voice in government. But after decades of the long sleep. the advent of new commumications and the Internet in the 1990s were a rude awakening." Mr. Kerr's Japan is indeed a dark place, a sort of James Cameron meets Franz Kafka nightmare dreamt by dim-witted, self-preserving bureaucrats. And although Mr. Kerr does an excellent job of diagnosing the disease, he shies away from offering remedies. Indeed, the pessimism that pervades the book seems to exclude the possibility that political and economic reform of the kind proposed by Japan's new Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi could have any effect other than plunging the country into a deeper mess.

Nonetheless, "Dogs and Demons" (Hill and Wane, 432 pages, $27) is a must-read for anyone. with even a cursory interest in the rise and continued fall of postwar Japan. As for the intriguing title. you'll have to read the book to find out why Mr. Kerr chose it-yet another of his many engrossing anecdotes.

James Fallows Atlantic, 2001 Jun 21~Jul 6

A six-part exchange with Alex Kerr, the author of Dogs and Demons: Tales From the Dark Side of Japan

From: James Fallows

To: Alex Kerr

Subject: The true Japan

Dear Alex (if I may):

Dogs and Demons: Tales From the Dark Side of Japan

by Alex Kerr

Hill and Wang

Thanks for joining this exchange, and thanks for writing the book. While reading it, I was struck both by material that was very fresh and by themes that were very familiar. I mean both points in a positive sense. The facts, anecdotes, and revelations will strike most readers as fresh and new. At least many of them struck me that way—most of all, your use of Japan's modern architecture as a symbol of what you think is more generally askew in modern Japan. Many of your themes were, to me, familiar in that they rang true to my own experience in Japan a dozen years ago—not because they're similar to what we usually read in the Western press. On the contrary, one of the reasons your book deserves attention from a Western readership is precisely how different it sounds from the run of general reporting about Japan.

Now a word of summary about this book, for readers who haven't seen it or who may not have been following the furor about coverage-from-Japan over the last decade or so.

The "dogs and demons" of your title are drawn from a Chinese parable, the point of which is that the grotesque, exceptional, and extreme aspects of a society—the "demons"—are easy to describe and depict. It is the routine, everyday, taken-for-granted details of life—the "dogs"—that pose real challenges to the artist. Especially in the last decade, Japan has entered Western consciousness, or at least the Western news system, mainly during "demon" episodes—not times when Japan is seen as acting "demonic," but when something truly exceptional is going on there, from an outbreak of violence to a new wave of bankruptcies.

The point of this book instead is to describe the day-by-day, rarely reported operating realities of modern Japan that are starkly evident to anyone who lives there but that somehow fade out of the Western mental, and above all journalistic, picture of Japanese life. When I first went to Japan, in the mid 1980s, I was initially shocked by one of those realities: how difficult and materially constrained work and residential life were for the average Japanese person, during a time when everything you read about the Japanese economy emphasized its steady rise to greatness. If anything, American readers have absorbed this lesson about the trials of life in Japan too well. Through the last five years they have tended to write off Japan as an utter failure—this is part of a century-long cycle of Americans first under- and then over-estimating the achievements and capacities of Japan.

Much of your book is organized around a different sort of surprise—how aesthetically unpleasant modern Japan has become, and what larger lessons may be derived from that. We'll save for later exchanges exactly what those lessons might be.

My hope in this opening round is to draw you out on some of the ways in which your analysis most dramatically differs from standard reporting, and to ask you why you think Western reporters in Japan so rarely offer the kind of perspective you've provided here. In later rounds I'll push you on a few parts of your analysis that I found less convincing or less fully backed-up than the rest. But those will be secondary cavils. This is a fascinating, artfully written book, which sounds as if you want to grab the reader by the lapels and make sure your case is heard.

What's different about your book? I assume you'll agree that the typical article about Japan in the U.S. press is not really about Japan at all. Instead it uses Japan as a foil for arguments the writer really wants to make about Western business practices, the American educational system, the mission of the U.S. military in the Pacific, or some similar theme. In a sense this got its start in the immediate post-World War II period, when protective U.S. diplomats projected an unrealistically meek and gentle view of Emperor Hirohito (a.k.a. the "Showa emperor" in Japanese terminology) and by extension of his people. Herbert Bix's magnificent book about Hirohito, Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, which won all the major literary prizes last year, suggests that even at the time, U.S. officials should have known that the Emperor had not been a harmless amateur scientist during the war but instead was an actively involved leader of the military effort. But conveying that actual truth seemed less important than offering the image of Sayonara-era Japan that would allow the U.S. and Japan to work together in the early Cold War years—and that would keep the Emperor on the throne. And so it has been, with differences in motivation and theme, through many decades of coverage from Japan. The nation has seemed interesting mainly to the extent that it could advance arguments about U.S. policy. In the past few years Japan has disappeared from America's mental map—except to be laughed at from time to time.

What I love about the tone of indignation in your book is that it arises from taking Japan itself seriously. You're on the warpath—but not on behalf of Western exporters who can't pierce the Japanese markets, or Western diplomats who can't get the Japanese government to play a larger international role. Instead you're angry on behalf of the people who actually live in Japan, and who suffer most of the consequences of its bureaucratized, quasi-democratic system.

Enough of this stage-setting. Let me introduce the single idea that will seem most startling to the average Western reader and ask you to elaborate on it. A real masterstroke of your book, I think, is the idea of organizing it around an expos้ of ... the construction industry! Let other people talk about the latest slick innovation from Sony. You argue that the backward, corrupt, totally un-chic business of building dams, extending roads, and laying down concrete is the key to understanding what's wrong with the entire country.

The single most startling fact in your book is that Japan, whose land area is only 4 percent as large as that of the United States, each year produces and uses more concrete than America does. ("This means that Japan lays about thirty times as much per square foot as the United States.")

And the single most startling assertion, at least for those who have not spent much time in Japan, is that "Japan has become arguably the world's ugliest country."

To me, this judgment rings absolutely true. While living near Tokyo I came to love the bustle, intensity, and surprise-around-every-corner nature of the city, but I rarely stopped wondering how so much prosperity (in those times) could have led to such a combination of kitsch and sheer eyesore. But I also know the judgment is surprising. Surprising at a surface level, because it's not what we see or read day by day. And absolutely shocking at a deeper level, because for all the East-West tensions through the decades, the one trait for which Japan has been most universally admired is the elegance of its artistic tradition. My walls are still decorated with ukioye, the graceful old watercolors of Japan. From the austere beauty of torii gates to the stylishness even of sumo wrestlers, this is a culture that, over the years, seems to have had a more refined sense of design than any other you can name.

So how can it be that modern Japan is an aesthetic disaster? I am asking you, now, for the benefit of onlookers who have not yet read your book, to sum up the case.

How could the civilization that epitomized beautiful design have produced the ugliest modern cities? Why does this matter? Do the citizens of Japan seem to care about it as much as you do? And why haven't we read about it except in your book?

Looking forward to your answers,

Jim Fallows

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Atlantic Unbound | June 21, 2001

fallows@large | Dialogues with James Fallows

From: Alex Kerr

To: James Fallows

Subject: Re: The true Japan

Dear Jim,

Every Japanese letter begins with a comment about the weather, so I must tell you that I'm writing this e-mail from my old thatched farmhouse in Iya Valley on the island of Shikoku, where rain is pouring down and mists?looking just like those zig-zag swatches of cloud you see so often on old screens?are rising from the valley, swirling together and disappearing again. ?It's my little bit of paradise, the beautiful Japan we all dream of.

You have no idea how I appreciate this opportunity to discuss Dogs and Demons with you?it gives me the forum I've been longing for to launch a fierce counter-attack against my critics! Well, there's a little of that, I must admit, but mainly it's a chance to talk about my supporters, that is to say the people for whom this book rings true and for whom it matters. I'm honored that you appear to be among them.

I'm starting right out by talking about this group of people because their existence underlies everything I've written. You ask if the citizens of Japan care about these themes as much as I do, and the answer is a resounding yes. Not everyone, of course. As in every country, a complacent majority rules. But there is here a substratum who are deeply disappointed with their nation?to the point of heartbreak. In my case, I've lived here so long (on and off since 1964, when I came as a child with my parents) that my feelings about Japan are strong indeed.

There is a real conflict going on right now in Japan between the forces of change and the old bureaucratic systems that have ruled for so long. The public is aware that this is a do-or-die moment, and this is why the new maverick Prime Minister Koizumi is so incredibly popular?more popular than any Japanese politician has ever been in modern history. People realize that Japan needs to change, but most are not aware of the details of the system that are strangling the nation. To turn these systems around will require a revolution in thinking that can only come after people look clearly at their circumstances and understand what is going on around them. That was what I set out to do in this book, to show the reality for what it is. This is my gift to the revolution.

But let's step back a bit from ringing words like "revolution." Many readers must wonder what is all this trouble I'm talking about. Isn't Kyoto a charming city filled with quaint wooden shops, rock gardens, and exquisite temples (not to mention geisha busily writing their memoirs)? Well, no, the sad reality is that the world heritage sites were preserved, but the city itself has been nearly wiped out in the past few decades. What's left in the city where people actually live is a conglomeration of concrete boxes, flashing neon signs, treeless streets, tangles of telephone wires, aluminum, chrome, and plastic. Kyoto has become one of the world's drearier urban landscapes, on a par with some industrial cities in China.

Tourism as an industry is a conspicuous failure?to the point that more people visit Croatia and Tunisia every year than Japan. Foreigners mostly avoid Kyoto, except those determined to do their "cultural duty." Meanwhile, the Japanese are also starting to avoid Kyoto?people prefer to tour theme parks like Universal Studios in Osaka, and millions more are flying abroad and escaping Japan altogether.

I bring up Kyoto as one example of an environment that has been mismanaged in a way almost beyond imagining in the West. An even worse fate has befallen the countryside, for here a mammoth construction industry (the largest in the world) every year gobbles up trillions of yen in government subsidies to build. Anything. Roads to nowhere in the mountains, bridges to uninhabited islands, empty "utopian cities" on harbor landfill, grim "resorts" that look something like a People's Palace in Communist Bulgaria, erosion control on mountains and beaches where nobody lives....

This brings me to your question: How did it happen? How could the country of "love of nature" turn on its own land with tooth and claw? How could the people who had "refined aesthetics" as their very birthright create and live in cheap houses, drab hotels, shabby cities?

It came about because of what I call the "victory of the industrial mode." When Japan opened up and modernized in the 1860s, the response to the threat from the Western powers was to throw all the energies of the state into building a strong manufacturing base. The loss in World War II only strengthened the leadership's resolve in this regard?if Japan's industrial base had been stronger, perhaps Japan might even have won the war.

So the overwhelming emphasis on building and making things goes on. Meanwhile everything else has been sacrificed: universities withered because the goal of education was to train people to be company drones, not to think. The legal system never developed means of restraining industrial excess such as toxic waste; nor did a non-profit sector develop. The landscape disappeared under cement. The financial system decayed due to a policy that funneled the nation's savings at zero percent interest to industry. And the culture suffered because very little was taught or studied that didn't bear on making things on an assembly line.

It's been going on a long time?a century and a half. In your book Looking at the Sun you described the complex of ideas underlying Japan's modern history in a chapter called "The Drive to Catch Up," the title of which says it all. The problem is that Japan never felt that it caught up. Policies that are completely out of line with the needs of Japan's society in the twenty-first century go on and on, and it seems almost impossible to stop or even slow them. In the process it wasn't only traditional aesthetics or love of nature that was skewed. Everything was skewed.

Why haven't we heard this from writers on Japan before? It's because Japan, for many who study it, becomes a religion to which people convert. They become true believers in Japan's cinema, architecture, the Ministry of Finance, or robotized factories?and the next step is to become a missionary preaching Japan's superior achievement. Obviously there is much to praise in Japan's modern development. But with a few exceptions such as yourself or Karel van Wolferen, Japan experts (especially cultural authorities) have almost universally shown us the asset side of the ledger and not the debit one.

And now I can finally talk about my critics. In a radio discussion recently with a Harvard professor, I brought up the fact that Japan had concreted 60 percent of its entire shoreline. That's because Japan chose to place its steel mills along the shore, and this brought tremendous profits to the nation, he hastened to explain. Well, the steel mills account for a fraction of one percent of the concreting. What about the other 59.9 percent? The telling thing was the professor's instinctive, almost pathetic, urge to justify Japan in its follies.

There's something else going on. One of my reviewers, another distinguished academic, dismissed the construction frenzy with the phrase "environmental insouciance." That's an interesting choice of words. Insouciance, to me, implies a child thumbing his nose at a straight-laced adult, something silly, even trivial. If they concreted over the state of Massachusetts, however, would this professor have viewed it with insouciance, I wonder, or would he be screaming bloody murder? There is an unspoken assumption that the Japanese are different and therefore need not lay claim to the quality of life that we take for granted in the West. It's a profound type of condescension.

Which brings me to your question: Why does it matter? I would say that from a universal standpoint, for the good of mankind, it's important that every nation preserve its cultural patrimony and protect its environment. When a powerful and wealthy country like Japan goes dramatically in the opposite direction, this is surely of concern to us all.

Within Japan it matters because Japan's present path is not something that most of its citizens chose or approve of. The agonized comments about Japan that you read in my book are taken from hundreds of hours of conversation and numerous books and articles spoken or written by Japanese. For millions of people within Japan, these issues matter.

Finally, despite the passionate tone of Dogs and Demons, it's a fact that beautiful mountain villages, lovely temples, interesting modern architecture, so many things of cultural value?even geisha writing memoirs in Kyoto?do still exist. I'm writing from one such Shangri La village at this moment. But these things have a limited lifespan, and they are truly few and far between. Ugliness is never far behind, and it's gaining rapidly. If fundamental change comes to Japan, what remains of beauty and value can be saved, and this gives me hope.

Well, the rain is still falling, and so is the soot from the rafters. I think I'll stop here. Please forgive my insouciance.

Best wishes,

Alex Kerr

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Atlantic Unbound | June 26, 2001

fallows@large | Dialogues with James Fallows

From: James Fallows

To: Alex Kerr

Subject: The true Japan - Part Two

Dear Alex:

Ah, the weather paragraphs. It all comes back to me now! When my family was living in Yokohama, my wife and I used to marvel at the ways in which we would unknowingly blunder each day. One of them that took me months to figure out was my failure to include preliminary chat about the weather in the first few moments of meeting a Japanese person or the first few lines of a letter. Have you read Edward Seidensticker's collection of essays, This Country Japan? It's been almost fifteen years since I looked at it, but I think I remember one poignant chapter composed of fictional letters between a young Japanese woman and an older American man. Each letter began, of course, with a discussion of the season. These served as markers for the change from springlike warmth to chill between the two of them.

So let me say that it is delightfully sunny now in Berkeley, as it is through most of the year, but as I look across the San Francisco Bay toward the city, I can see the evening bank of fog beginning to move this way. Midsummer can oddly be the coldest season in San Francisco. As the sun beats down on the interior valleys of the state, just beyond the gentle Berkeley hills, it superheats both land and air and creates rising currents, which in turn draw in the cool, cloudy air from the sea. Already the tips of the Golden Gate are the only part of the bridge visible above the fog, and Alcatraz is about to disappear. Yet when I think of the clammy misery of the tsuyu, or month-long "rainy season" that must be underway in Japan just now, I am newly grateful for the comforts of the coast on this side of the Pacific.

Enough of that! For this installment I'd like to take you in a slightly different direction, away from specific discussion of your book and toward larger explanation of what's been happening in Japan. What I'll be asking about is indirectly connected to your book, since after all you are describing how Japan struggled to "catch up" economically with the Western world and what happened when it did. But I'd like to summon you as a kind of expert witness. You've been in Japan during its economic ascent in the 1980s and its perceived stagnation, even collapse, since then. Let me tell you what I find puzzling about this sequence, in hopes that you can tell us how it has looked on the scene.

Let's step back fifteen years. You probably remember, but many readers won't, that in the fall of 1985 the "Plaza Hotel Agreement" began an enormous change in relations between Japan and the rest of the world. Through the early 1980s, Japan was piling up trade surpluses like crazy. The yen was still cheap?an incredible 250 or so to the dollar! At the Plaza Hotel, James Baker, then the Treasury Secretary, agreed with his Japanese counterparts to start moving the yen up and the dollar down. (His main counterpart was Noburu Takeshita, Finance Minister of the time, later Prime Minister, epitome of the deal-making, patronage-dispensing career Japanese politician.)

Less than a year after the Plaza agreement, the yen had doubled in value against the dollar. I know! I'd calculated all my expenses for living in Japan in the summer of 1985, at 250-per-dollar, and when I got there in early 1986 everything cost twice as much as I expected (or could afford).

The point of jacking up the yen's value was, of course, to try to equalize trade flows?fewer Toyotas into the United States, more Intel chips into Japan. But its main effect was for a brief time to make Japan seemingly the richest, and certainly the costliest, nation on earth. With their mighty yen Japanese corporations could buy up French art, American companies, Asian resorts, and practically anything else they chose.

What they didn't do, contrary to most expectations, was start importing dramatically more or exporting dramatically less. Exactly why this was so is part of what I want to ask you about. But nearly everything about subsequent Japanese history seems traceable to those two or three years after the Plaza agreement, when Japan became on paper stupendously rich but didn't behave the way the world's finance ministers had foreseen.

How is it traceable? Well, that's what the argument is about. Let me tell you, first, what conventional American wisdom now holds; then give you my hypothesis, as someone who has not visited Japan in four years. Your job will be to tell us what has really gone on.

To the extent Americans think about Japan anymore, they think: it had its boom back in the 1980s, a lot of alarmists (like Fallows of The Atlantic) got worked up about Japan's potential, but since then it has fallen flat on its face as America has recovered. Japan is politically paralyzed, despite minor blips of excitement about reform; it has no influence in the world; no one pays attention to its pop culture; it can't clean up the bad loans from its banking system; its managers are killing themselves. Meanwhile, America is the undisputed world titan, the dollar is stronger than ever, we have led several waves of entrepreneurship and wealth-creation, and despite the recent slowdown we're in shape any other country should envy. In short: the idea that there was ever anything interesting, instructive, or above all menacing about the "Japanese model" is preposterous.

My own view, you won't be surprised to hear, is at odds with this. To my mind, the fundamental argument that began fifteen years ago was not whether the Japanese model of economics was superior to the Western model. Rather, the question was whether it was different. Now that Japan looks weak, everyone seems willing to concede that point. Sure, Japan is different?and worse! But at the time, "Japanese version of capitalism" amounted to fighting words. Everyone could agree that operational details and principles differed between Japan and America. Shareholders had much less influence in Japan. Government planners had much more. Consumers did well in the United States and poorly in Japan. The American ideal?as long as it could be sustained?was a trade deficit, since that allowed us to consume more than we actually produced. The Japanese ideal?as long as it could be sustained?was a trade surplus, since that allowed more people to stay at work than the country's own purchases could support.

The real disagreement about Japan was whether these differences should be taken as signs of Japan's "immaturity," which would by definition melt away as Japan converged on the American model. Or whether, on the contrary, Japan might for years and years operate an economic system that was recognizably capitalist but also different in its goals and methods from the American version.

I contend that the years have vindicated the "different system" rather than "converging systems" view of Japan. Some things have surprised me, compared to what I would have expected a decade ago. The improvement in America's overall social-political-productive fiber has been better than I expected?and better than practically anyone else foresaw. Hey, in 1994 Bill Gates didn't know the Internet was coming! I've been surprised by how fractious Korea has remained over the years. But the only thing that has surprised me about the Japanese system is that it is even more rigid than I had foreseen. A dozen years ago, mainstream American economists argued that Japan would "inevitably" switch to a more consumer-driven, open, liberalized economy. But the forces backing up the old, closed ways are even stronger than almost any observers claimed. The American press swooned in 1993, when Morihiro Hosokawa (remember him?) stormed in as a fresh, "reform" leader of the country. That "Tokyo spring" lasted about as long as the Prague Spring of 1968. And still the system grinds on: emitting exports, providing jobs, bilking its consumers, and creating adjustment problems (through chronic surpluses) for the world economic system.

In short: most of America sees Japan as a pathetic failure, a less threatening version of the old Soviet Bloc states. I see its struggles in the 2000s as directly connected to its allegiance to a "different" model of capitalism, and I still see little evidence that the models are about to converge.

So could you please tell us: How should we think about the past decade's worth of struggles in Japan? Does the latest political "upheaval" portend a more serious change? Are the chronically pent-up forces?unhappy "salarymen," unhappy women, unhappy and overworked students?sufficient to change the nature of the system now? Is the prevailing, dismissive view from the United States warranted?

As I turn from my computer, I see the sun, fat and red, slipping beneath the bank of fog to the west. Across the broad Pacific you are sitting in the rain. Glad there's no tsuyu here.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Atlantic Unbound | June 26, 2001

fallows@large | Dialogues with James Fallows

From: Alex Kerr

To: James Fallows

Subject: Re: The true Japan - Part Two

Dear Jim,

We've had a break in the clouds after a solid week of rain. Actually I enjoy the rainy season and always try to plan to be in Japan for it?here in Iya, as the mists come flying out of the valleys, opening up and closing, thinning and thickening with incredible speed, you feel like you're sitting in a boiling cauldron of vapor.

But today it's sunny, the sky is blue, the mud is drying out, the air is crisp. It's only a short window in the rainy season, however. Long damp days?when newspapers get soggy and sag while just sitting on a desk, and you wake up in the morning to find your shoes covered with white mold?are coming again soon.

It's too bad you and I can't correspond solely about the weather! Instead I've got to answer your difficult questions, and this time you've asked the most difficult one of all. It strikes right at the core of the debate over Japan's success and future world role: namely, is Japan fundamentally different from other countries, and is this difference sustainable?maybe even an advantage?over the long term?

I remember back in May, 1989, when I read your article in The Atlantic entitled "Containing Japan." I could hardly contain my excitement. As my memory serves me, you argued that Japan has perfected an economic system that does not follow policies of free trade and rationalized finance that are taken for granted in the rest of the world?and it's useless to expect Japan to change. It won't. Instead, you suggested that America "contain" Japan by taking steps such as requiring reciprocal trade in military contracts, setting up a system of "import certificates," and so on. I was excited because you were the first writer I had come across who openly admitted that Japan was different?and would not change.

Well, your words went almost completely unheeded. American trade negotiators went on insisting that Japan open up to imports; Time and Newsweek continued every year to publish breathless issues about the free-spirited Japanese Youth and how they were going to transform the nation overnight. But Japan never changed. Meanwhile, in America, new Administrations arrived in Washington every few years, each one more ignorant than the last with regard to Asia, and so we never took any serious steps to contain Japan.

And yet America boomed and Japan stagnated. And this is perhaps the core point of Dogs and Demons (the one that most upsets the old-line Japanologists): Japan's troubles are not merely economic, but reflected in a degraded environment and impoverished intellectual and cultural life. All this, in spite of having every "unfair advantage." Why?

I think several things are going on. One has to do with the internal dynamics of Japan's different system. The thing is that it worked all too well. I think it's a case of "be careful what you wish for, because you might get it." Japan's export machine relied on repressing consumers. Well, today they're well and truly repressed. Japanese finance fed money to industry at no interest and did not require companies to make profits. The result is that stocks, bonds, and real estate do not make returns?that is, money makes no money in Japan. And companies don't make profits. Meanwhile, in myriad little ways, Japan resisted a role for foreigners in its culture and economy, and so the foreigners stayed away. Today they don't travel to Japan (Japan is thirty-second in the world as a tourist destination), nor do they live there except in tiny enclaves in Tokyo, Osaka, and Kyoto. Japan chose to go it alone. This means that Japan is doomed to do everything by itself?re-inventing the wheel constantly.

Remember the story of the polio vaccine which you told in Looking at the Sun? In order to support domestic pharmaceuticals, the Ministry of Health and Welfare prevents foreign companies from selling new medicines in Japan until local firms come up with zoroyaku, or copycat medicines. Zoroyaku means "one after another," because they are produced one after another as reverse-engineered copies, often with poor efficacy or even terrible side effects. In the case of the polio vaccine, it killed dozens of children in the 1980s and yet the government never lifted a finger to stop it. Protected in this way, domestic pharmaceuticals no longer know how to create advanced medicines; nor are there protocols for testing. Japan's doctors get by with second-rate medications, hand-me-downs from abroad, essentially. And Japan's pharmaceuticals have almost no world presence.

Repeat this scenario in thousands of industries and government agencies, and what is happening over time is that everything is becoming zoroyaku. Second-rate roads, hotels, museums, houses?even washing-machines, door hinges, and toothpaste. Japan wanted only Japanese toothpaste, so it got Japanese toothpaste.

All that said, the Japanese system brought tremendous advantages, as we all know, making Japan one of the world's richest and most powerful nations. We could argue the merits and demerits of that system forever.

But there's another thing going on. Let's assume that Japan's system was wonderful, invincible, a model for us all. There was one little flaw: and that was the lack of change itself. Back in the 1980s many thought of this as a strength compared to the chaotic and permissive West. The thing is, as Machiavelli pointed out so long ago, no system, not the finest ever devised in any time or place, can continue to thrive without change.

Most of Japan's modern troubles?the construction frenzy (government budgets on automatic pilot), the financial bubble (securities that yield no returns), lackluster Internet and software industries (companies that discourage creative thinking and give no chances to young entrepreneurs)?came about because of an inability to change. Policies set in motion in the 1950s live on today, despite a huge divergence from both domestic needs and international realities.

America, it turned out, did the cruelest thing of all by doing nothing. With the U.S. not attempting to "contain Japan" (except some half-hearted trade negotiations), the nation felt no need to change. Meanwhile, the world shifted into an entirely new paradigm, not only of wealth creation (which moved away from manufacturing hard goods to software and intellectual property), but also of culture (which blossomed with a new free flow of people and ideas across international boundaries). Oblivious to all this, Japan's government ministries, colleges, and big industry went on doing everything the old time-tested Japanese way. So the stock market collapsed, the mountains and rivers got covered with cement.

So what about the new Prime Minister and his reformist government? Is a big revamping finally on the way? Certainly there's more awareness of the need for change among the public than I have felt in all my years in Japan. Some of the new cabinet's proposals, such as those mandating access to information in public agencies, have the potential to transform the machinery of government.

It's an exciting time to be here. Entrenched bureaucrats will go to surprising lengths to fight these reforms, as we can see in the mudslinging between Foreign Minister Makiko Tanaka and her staff, who have released sensitive details of diplomatic talks to the press in order to embarrass her. There's a real fight going on, and it makes for entertaining television, if nothing else.

I would like to be optimistic. But I fear that these heady times of change may be as fleeting as our short spell of sunlight here in Iya. Some long damp days are still ahead. The problem is that Japan is addicted to these old systems. Stop concreting the countryside and millions of people will be thrown out of work. Rationalize securities so that they yield returns, and the value of government bonds plummets, banks fail, the whole financial world could crumble. The pain of withdrawal from the various opiates will be severe, and despite all the rhetoric, I don't know that the public or politicians are willing to accept the pain.

Meanwhile, life here in Japan isn't all that bad. We're not talking North Korea, after all. Most people live reasonably comfortable lives: they have a toaster, a car, a refrigerator, plenty to eat, and the amenities of advanced societies?hospitals, schools for their children, trains that run on time. Even the toothpaste sort of works. There's a deep problem with quality?the houses are cramped, cities ugly, natural environment trashed?but life goes on at a material level that many in the world's developing countries would envy. You wrote back in 1989, "Through the century and a half in which America has been dealing with Japan, 'fundamental change' has always been right around the corner, but change has come only when the country has faced dire emergencies: the need to catch up with the industrialized West in the Meiji era, the devastation at the end of the Second World War."

So are we now facing a dire emergency? I think not. This is why I use the "boiled frog" metaphor for Japan: if you drop a frog in boiling water, he'll be scalded and jump out, but if you set him in lukewarm water and slowly turn up the heat, he'll sit there contentedly and get cooked.

Let's think about it. Suppose Japan suffered a truly disastrous economic downturn and the GDP dropped by 20 percent, which is almost inconceivable. Japan would still be one of the world's wealthiest countries! And I'm definitely not predicting anything like such a crash. Rather, I think Japan, with its strong industrial and technological resources, will do just fine?as an exporter of goods. In this respect, Americans are very wrong if they think they can dismiss Japan as a failure economically. It's still a formidable competitor. After all, the entire "different" system, with all its quirks and sacrifices, was set up for one goal: expansionist export industry. That goal is still in place, as is the system to support it.

Therefore the big reforms of Koizumi's administration are likely to amount to a little oiling of the wheels, rather than a thorough overhaul. But who knows? Gorbachev thought he was going to introduce just a little glasnost, and look what happened! When you begin to make reforms in a system as rigid and in some ways fragile as Japan's or the USSR's, there can be some big surprises.

Well, so much for Japan, which seems far away from up here on a mountainside in Iya. It's nighttime now, and the moths are flying in, huge celadon green ones lying flat on our black wooden floors. We only get these on clear nights, so I'll enjoy them until the rains start again.

Best wishes,

Alex

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Atlantic Unbound | July 6, 2001

fallows@large | Dialogues with James Fallows

From: James Fallows

To: Alex Kerr

Subject: The true Japan - Part Three

Dear Alex:

I started out writing another weather paragraph, but I couldn't finish it with a straight face. For one thing, the weather here in Berkeley is the same old sunny perfection as always. Moreover, starting out this way makes me feel like an American tourist in England pretending to be local by saying "Ta!" (instead of thank you) to shopkeepers and using phrases like "in hospital" or "on holiday." Unlike me, you are a genuine product of the culture of weather paragraphs, so I'll be disappointed if you don't come back with another one. But I must revert to my frontierish American instincts and say, We're down to the last round, and it's time for a summing up.

My plan is to ask you a few questions that I think may clarify your views for those who have followed this discussion but have not (yet!) read your book. And, for the record, I do hope people will get and read the book. It's gracefully written and well-informed. It's full of original observations. It will give American readers a context for absorbing the otherwise atomistic news bulletins they receive about Japan?"economic slump continues" one day, "political reform on the horizon" the next.

My first question is about the fundamental argument you're making in this book. We've discussed a variety of topics that may not seem related to one another. For instance, if you were writing about twenty-first century America, you wouldn't necessarily try to explain George W. Bush's election by describing the office-building architecture of Manhattan. But in our discussion, and much more so in your book, you make a comparable link, plus combining a whole barrelful of different subjects. The one that seems most heartfelt is your aesthetic critique of Japan: why the buildings are so ugly, why Kyoto looks more and more like Houston, and how a visually refined culture began producing dross. But you also have an extended administrative and budgetary analysis of the Ministry of Construction. You talk about the agony of being a Japanese student. You go into the role of the vivid comic books known as manga, as well as the difficulties facing the new "reform" leadership in Japan. What you say about the concrete-pouring industry in Japan could be a magazine article on its own.

The question is: How does all this fit together? Let's imagine that you're on Virtual Book Tour right now, and you have to explain in a paragraph why the political nature of Japan has led to the visual results you describe. If you tell us that totalitarian North Korea has totalitarian-looking buildings, that we can understand. But Japan's not quite the same, is it?

And here's a follow-up question. You explain, both in the book and in a previous dispatch, the difficulties Japan has had in turning off the "catch up" machine. In the mid nineteenth century, and again after World War II, the country devoted tremendous resources to achieving technological and economic parity with the Western world. That meant what Americans would think of as a permanent wartime economy, even when no actual hostilities were underway. The question: did this part of political history necessarily or naturally lead to the concrete-covered landscape you describe? Or was that some kind of unlucky accident?

For the next question, I'm reprising something I asked the first time around, because it remains so fundamentally puzzling. It involves the "natural" design sensibilities of Japan.

Of course it is reprehensible to speak of different cultures as having "natural" traits of any sort. But if you had to identify the single characteristic on which Japan has led the world, it would certainly be the sense of design. Take almost any aspect of Japanese life over the centuries, and you are likely to find breathtaking elegance of conception and execution. Buildings. Clothing. Weapons. Statues. Paintings. Calligraphy. Gardens. Anything else you can name. This is why Western artists embraced Japanese design a hundred years ago?and it is why your main argument about an ugly, kitschy-looking civilization is so startling now.

And my question is, again: How can this be? I ask this time not in a political sense but in a human one. The love of automobiles and guns is not as historically rooted in America as traditional design was in Japan, but nonetheless it's hard to imagine an America with neither guns nor cars?or France without wine, or Italy without pasta. How do you think average Japanese people reconcile what they know to be the glory of their civilization with the way you say they now live?

This next question is a real softball. The latest attention your book has received in the U.S. press was a review by Ian Buruma in The New York Review of Books. Buruma is a longtime, skilled observer of Asia who, despite his other virtues, has never been known for generosity to others on the same beat. (Disclosure: I've had run-ins with him.) You mentioned in our first round your glee, which any book-writer can understand, about having a chance to reply to critics. By his standards Buruma was not that tough on your book. But what do you most wish readers of that review also knew about your argument? And, while you're at it, is there anything you wish you'd added, cut, or stated differently in the book?

Final question: If we accept your argument and analysis, what do you think we should expect from Japan in the long run? That is, does the record of the past decade, in which Japan has stewed in its own problems, tell us anything useful about the next? Obviously none of us knows what's going to happen?but if you had to bet, would you choose more of the same in the next few years, or something basically different?

Thanks for your patience and participation. I look forward to meeting you in Japan, where we can start by discussing the gentle rain.

James Fallows

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Atlantic Unbound | July 6, 2001

fallows@large | Dialogues with James Fallows

From: Alex Kerr

To: James Fallows

Subject: Re: The true Japan - Part Three

Dear Jim,

Zenryaku. That means "dispensing with preliminaries," and it's a handy expression you can use in Japanese letters (very popular in e-mail) in order to get around writing another paragraph about the weather. So I'll not say much about my garden in Kameoka (outside of Kyoto), where I am now, looking out at feathery maple leaves glistening in the night rain.

Instead, to your first question: How does it all fit together? How does Japan's bureaucratic and political system relate to the ugliness of its modern environment? This touches on one of my goals in writing Dogs and Demons. Typically, writing about Japan falls into two camps: economical/political and cultural. The former group tend to be hard-nosed professionals, and while they have their various enthusiasms (in the eighties everyone loved MITI, the Ministry of International Trade and Industry, in the nineties they lost their hearts to the Ministry of Finance), they do tend to look at Japan with an analytical and critical eye. Then there are the cultural writers, who specialize in Zen, architecture, cinema, manga comics, rock gardens, and so forth. These tend to be full-fledged converts dedicated to preaching the high aesthetic and moral value of Japanese arts to the world. Most of the political writers have little or no interest in arts or the natural environment; and the cultural writers don't read or understand the financial page of the newspaper.

In my case, because of a quirk in my background, namely the fact that Trammell Crow drew me into the business world in the 1980s, I had experienced both worlds. So I tried to combine them. Perhaps I was too ambitious. But what is absolutely fascinating to me about modern Japan is the way in which exactly the same troubles bedevil every aspect of society. The reason the banks are failing is the same reason Japan can no longer produce movies for adults?or stop concreting the countryside.

Here, in a nutshell, is what I think happened: Japan had a wonderful formula for economic success in the 1950s and 1960s. There was a literate and well-educated work force?obedient, hard-working, and willing to sacrifice for the national good. It had an elaborate industrial structure that repressed imports and controlled the marketplace by keeping big firms big and small firms small. The government was in the hands of one party that stayed in power for generations. Meanwhile, true power was concentrated in the hands of elite bureaucrats who ruled quietly from behind the scenes. All was stable, all went like clockwork.

Unfortunately, there were a few missing pieces in the machinery. For one thing, Japan did not have a true democracy, which meant that the voice of the people was not heard. It didn't have an independent legal system. It didn't have a rational financial system. And there were no watchdogs on the bureaucrats.

All this is a recipe for "auto-pilot," which is essentially what happened. There was nobody to question or to provide new ideas, no winds from abroad, no community consciousness. Japan's systems froze. The rules and regulations got more and more complicated, and their reason for being grew farther and farther from the real needs of society. By the end of the twentieth century, Japan's ways of doing things had grown wildly removed from reality.

Hence we get stocks producing no dividends, roads going nowhere, dams built for no reason, bridges to uninhabited islands, universities that don't research or teach higher knowledge, companies routinely issuing false financial statements, untrained workmen pouring fissionable material out of buckets.

These things are indeed all related. They came about because Japan's systems were all too far-reaching and inflexible. The aim was stability. Stability, without change, became decay.

Another thing that happened in field after field was "addiction." The countryside is addicted to pouring cement. Banks depend for their very lives on zero interest deposits. Movie companies cannot shake their dependency on animated films for children. And architects survive on regular fixes of income from bombastic monuments. It's so hard to shake these addictions! Hence Japan is finding change excruciatingly difficult.

So, yes, architecture is related to banks and the stock market, and these are related in turn to the destruction of old cities, mountains, and seaside. It's the same sickness in different places.

Next you ask whether the concreting of the countryside was an inevitable part of Japan's political history. It's always interesting to speculate on "what if?" Before World War II, despite the military hysteria, there was a firm core to Japan's traditional culture, upheld by a wealthy land-holding class. The loss of the war (which led people to question all traditional values) and MacArthur's land redistribution had the effect of smashing this core. So perhaps if Japan had not rushed into war in the 1930s, its culture and environment might have survived in better shape. In a sense, today's environmental calamity could be viewed as a time-delayed result of the loss of the war.

After the war, if Japan had achieved true democracy, the nation might have been governed by politicians who did not depend on the rural vote, as the ruling LDP party has done these fifty years. So there may have been no need to flood villages with money from construction projects, thereby giving the countryside a gigantic New Deal.

But these things did happen. And once they were set in motion in the 1950s, then what we see now probably really was inevitable.

This brings me to your final two questions: Ian Buruma's review, and How Could This Be? That is, how could the nation that seems to have had aesthetic perfection as its very birthright sink into a culture of cheap industrial junk? I think I can answer them together.

First, Ian Buruma. As you know, I've been longing for a chance to reply to my critics, and there is no one I'd rather get my teeth into. But unfortunately, Buruma devoted most of the review to expounding his own personal idea of Japan's post-war history, and only tangentially mentioned my book, so there's not much I can say in reply. There is one important point, however, that I'd like to pass on to my readers. Buruma complains that I seem "obsessed" with foreign observers and old-line Japanologists who are preaching Japan's glory. "Who is he talking about?" he asks.

Alas, one of them is Buruma himself. While he is not preaching Japan's glory per se, he has fallen into the old trap of excusing Japan's failings by attacking the critic. It's endemic to this field. It used to be that critics of Japan, like Karel van Wolferen, were called "Japan bashers." That term is now out of vogue. The new approach is to dismiss the writer by suggesting that his comments are the result of some personal animus. Buruma talks of my tone of "personal hurt, something of the erstwhile Japanophile who feels spurned or let down."

Let's talk about this for a minute. The same sort of comment was made by an (unnamed) reviewer in The Economist. He (or she?) wrote, "Like so many foreigners who have adopted Japan and made it their home, affection eventually turns to frustration, anger even, as the subtle and inevitable exclusion by a culture that treasures its homogeneity starts to erode the foreigner's enthusiasm...."

Well, we know that disillusionment with Japan is a common pattern. And I would hardly deny that I'm disillusioned. However, I would argue that it's the same disillusionment that millions of Japanese feel with their own country. In 1997 I moved my base of operations to Bangkok. However I've kept my houses and my business here, and continue to spend several months of each year in Japan. My particular focus for these last few years has been the "Chiiori Project," an attempt to revive a remote mountain village in Iya Valley where I've had a home for thirty years, through sustainable tourism. Meanwhile I'm meeting with bankers in Tokyo for other purposes. Perhaps if Buruma had been involved on the ground?running a business, for example, rather than writing a column about economics; or planning and executing cultural events from backstage rather than sitting in the critic's chair, he too might have felt some of the Japanese people's disappointment himself. What is absurd is the assumption that it's due to a feeling that I was unfairly treated. Nowhere in any of my writings (Lost Japan, or Dogs and Demons) have I ever implied that I was excluded from anything!

I knew this would be a common reaction among foreign Japan observers, and thought I was mentally prepared for it, but it still surprises me to hear it from someone of Buruma's stature. There is a knee-jerk reaction that the only reason a foreigner would write critical things about Japan is because he's an outsider with a personal vendetta. The fact is that I was never "excluded" or "spurned" by Japanese society: I had (and have) good friends there, two lovely houses, a wonderful antique collection, a profitable company, was admitted into the inner circles of culture, and have been very well-treated by the media?and all of that is still here when I return from my home in Bangkok. I've never made a word of complaint about my personal situation in Japan, and why should I? Buruma (whom I've never met, and therefore wouldn't dream of guessing what his personal motives are) should have known better than to create an imaginary persona for me.

The reason I dwell on this point is that yes, I'm angry and disappointed, but my anger lies in what happened to Japan, not in what happened to me.